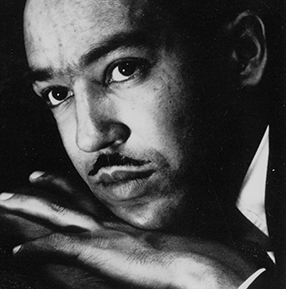

Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes was born February 1, 1902, in Joplin, Missouri. His parents divorced when he was a young child, and his father moved to Mexico.

He was raised by his grandmother until he was thirteen, when he moved to Lincoln, Illinois, to live with his mother and her husband, before the family eventually

settled in Cleveland, Ohio. It was in Lincoln that Hughes began writing poetry. After graduating from high school, he spent a year in Mexico followed by a year at Columbia

University in New York City. During this time, he held odd jobs such as assistant cook, launderer, and busboy. He also travelled to Africa and Europe working as a seaman.

In November 1924, he moved to Washington, D. C. Hughes’s first book of poetry, The Weary Blues, (Knopf, 1926) was published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1926. He finished his college

education at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania three years later. In 1930 his first novel, Not Without Laughter, (Knopf, 1930) won the Harmon gold medal for literature.

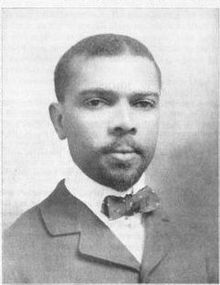

Hughes, who claimed Paul Lawrence Dunbar, Carl Sandburg, and Walt Whitman as his primary influences, is particularly known for his insightful, colorful portrayals of black life

in America from the twenties through the sixties. He wrote novels, short stories and plays, as well as poetry, and is also known for his engagement with the world of jazz and the

influence it had on his writing, as in his book-length poem Montage of a Dream Deferred (Holt, 1951). His life and work were enormously important in shaping the artistic contributions

of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. Unlike other notable black poets of the period—Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, and Countee Cullen—Hughes refused to differentiate between his personal

experience and the common experience of black America. He wanted to tell the stories of his people in ways that reflected their actual culture, including both their suffering and their

love of music, laughter, and language itself.

The critic Donald B. Gibson noted in the introduction to Modern Black Poets: A Collection of Critical Essays (Prentice Hall, 1973) that Hughes “differed from most of his predecessors among

black poets . . . in that he addressed his poetry to the people, specifically to black people. During the twenties when most American poets were turning inward, writing obscure and esoteric

poetry to an ever decreasing audience of readers, Hughes was turning outward, using language and themes, attitudes and ideas familiar to anyone who had the ability simply to read . . . Until the

time of his death, he spread his message humorously—though always seriously—to audiences throughout the country, having read his poetry to more people (possibly) than any other American poet.”

In addition to leaving us a large body of poetic work, Hughes wrote eleven plays and countless works of prose, including the well-known “Simple” books: Simple Speaks His Mind, (Simon and Schuster, 1950);

Simple Stakes a Claim, (Rinehart, 1957); Simple Takes a Wife, (Simon and Schuster, 1953); and Simple’s Uncle Sam (Hill and Wang, 1965). He edited the anthologies The Poetry of the Negro and The Book of Negro

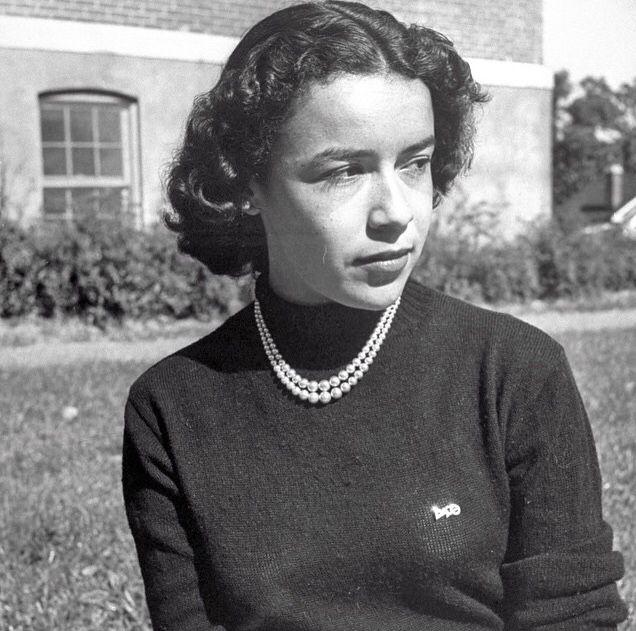

Folklore, wrote an acclaimed autobiography, The Big Sea (Knopf, 1940), and cowrote the play Mule Bone (HarperCollins, 1991) with Zora Neale Hurston.

Langston Hughes died of complications from prostate cancer on May 22, 1967, in New York City. In his memory, his residence at 20 East 127th Street in Harlem has been given landmark status by the New York City

Preservation Commission, and East 127th Street has been renamed “Langston Hughes Place.”